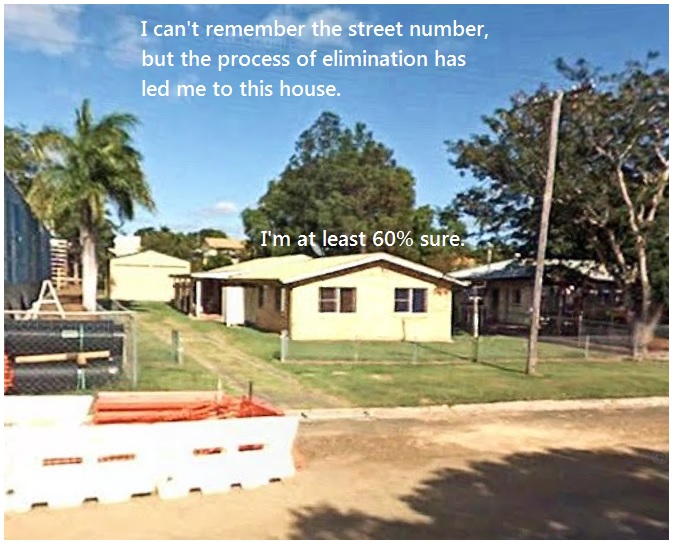

Yes, I know. There’s no street name. I’m sorry, I’m letting you down. It’s the first address for which I’m completely drawing a blank (SPOILER: it won’t be the last). I know the town, but any further details escape me. Even mum, who thus far has provided a great back-up memory bank, came up empty.

Luckily this story was never going to be entirely about the house itself: it’s also about a person.

I feel like I’ve introduced a lot of villains so far: Mrs Yudetsky, Mr & Mrs Fuckshit, the peanut butter bandits, a lazy kidnapper, the laws of gravity. And I haven’t even begun with Dale yet. So I figure it’s time to bring in at least one white hat.

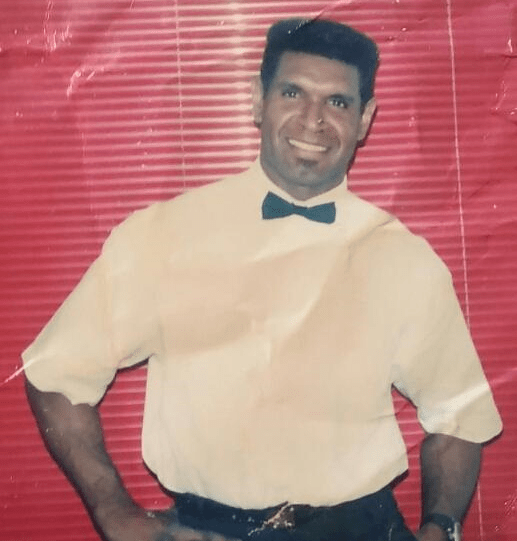

Meet Robby.

This is what Mum sent in response to my request for “old photos of Robby”. Mum thinks she’s hilaaaaaaaarious.

Robby is a dear, dear family friend. She’s practically family herself: her grandmother and my great-grandfather were childhood friends, whose parents had not-all-that-secretly hoped that they would marry each other. This didn’t happen, but they did stay friends, and our families have been intertwined ever since. It’s been about 150 years so far. Robby and mum became very close when Robby was 13 and mum was 23. That’s also around the time Robby and I bonded. As she likes to tell it:

“You were three years old and I knelt down in front of you and you RAN into my arms! You’ve been my treasure ever since.”

That last bit is 100% true to this very day. I am a 33 year old man, complete with a driver’s license and a beard and a browser history littered with pornography; but Robby still calls me “treasure”.

Proof: A message from Robby in 2014 in which I am called “treasure”. (And in which she gives me glowing praise. Not that that’s the only reason I picked this particular message. Ahem.)

The family entwinement continues apace, too: my sister and Robby’s daughter are now also close friends. So the family friendship looks like it’s easily going to round out at least two centuries.

But back to 1989: Robby had already been part of our lives for a few years by this point. But while we were in Mulgrave Street, Robby actually moved in with us. She had been in a bad situation, and coming to live with us was her way out.

Being that she is a) a clean freak, and b) a workhorse, immediately upon moving in she started acting like a live-in housekeeper. As mum left for work each day, Robby was making sure my sister and I were breakfasted and dressed, then she would bundle Lauren into the pram and walk me to school. She would be at the gates in the afternoon when school finished, where she would walk me home again, usually via a park. By the time mum came home from work, we were all bathed and pyjama-ed, and dinner was on the stove. In mum’s own words “it’s the closest to living like a movie star that I will ever experience.”

BUT HERE’S THE THING. While it might have been glamorous and utterly befitting my childhood snobbery (horses, internal staircases, now a live-in nanny? But of course), the glamour was slightly diminished by having mum, Dale, Lauren, Robby and I all squeezed into a two bedroom apartment.

And that’s how we ended up in Edmonton, and this is where my memory fails you. I’m sorry.

What I can tell you is that Edmonton is a little town outside Cairns. Well, it was: I think by now it might just be a suburb of Cairns. I remember that I went to Hambledon State School (evil, possible-witch teacher count: 0), and I remember we legitimately had a movie-style “fake” phone number: it started with “555”. It was never not funny to give the number out, but it did take some convincing to get pizzas delivered.

I do also remember being impressed by the size of the house we lived in. Compared with the space we’d been occupying it was positively palatial, but even on its own merits…it was still kind of palatial. The bathroom was like the foyer of a casino, all black tiles and spotlights. There was no need for a shower curtain, because the recess for it was so deep that water had no chance of getting out. After entering the shower cubicle you had to turn a corner and walk a few steps to get to where the water was. It was so big it had a bench built into the wall; presumably so one could have a rest and get their energy back before making the trek back out to the towel rail.

So while I can’t remember the address, or anything about my room, I do remember being amazed by the overall size of the house. And I distinctly remember excitedly telling anyone who would listen that the space between the front door and the kitchen bench was so wide I could do four whole cartwheels in a row.

In hindsight, I guess this is what mum means when she says she had an idea I was gay many years before I did. Measuring the width of a house in gymnastics, rather than in metres, does send some pretty clear messages.